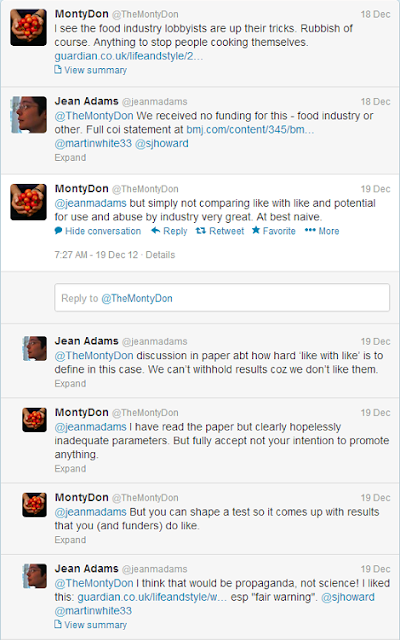

Is it more scary when Monty Don slags off your research on Twitter, or when a professor who you respect a lot asks you nicely to be a bit more careful with your not-quite-what-it-was-designed-for use of his carefully developed tool (also on Twitter)? How about both on one day?

What seems like a long time ago now, an MSc student emailed to ask if I’d be interested in chatting about an idea he had for a dissertation project.

His idea was simple: compare the nutritional quality of ready meals to celebrity chef meals. I don’t think the student (now graduate) in question would mind me saying that he’s not unfamiliar with a ready meal, or currently maintaining his weight within the recommended BMI range. Slightly fed up with being told his ready meal habit was bad for him, he was interested in finding out just how bad and whether it was any worse than the alternative that seemed to be in his face whenever he was eating his ready meals – something served up by Nigella, Jamie or Hugh.

In contrast, I and my co-supervisor were backing the celeb chefs. I don’t think I’ve ever eaten a ready meal, and it is possible that I have an affinity for glossy recipe books that has resulted in a collection that outgrew the kitchen bookcase some time ago. Scientists are neutral (not). We might be able to collect and analyse the data objectively, but it was clear what results each member of the research team was hoping to find.

The project was perfect for an MSc dissertation: clear research question, data collection primarily via the web, fairly straightforward analysis, no ethics permission required. We joked in supervision that the BMJ would love it.

And so it came to pass that the student collected and analysed his data, perhaps stretched the use of front of pack labelling for a good gimmicky visual a bit too far, got a good mark, and toddled off back to his real job promising to send us a draft of a paper sometime. Often those manuscripts never materialise. But lo! This one did. I wasn’t absolutely convinced that the BMJ really would love it, but we’d said they would and it seemed a shame not to try. They say ‘no’ pretty quickly.

I was mildly offended when the BMJ’s response to our rather serious and important piece of work was that it was “quirky” enough for their Christmas edition. Sure it was fun and sure I wasn’t quite convinced that it was good enough piece of work to be considered normal BMJ material. But there is a serious point here: lots of public health advice suggests that people should cook from scratch and implies this is better for you than eating ready meals. If you don’t know how to cook from scratch, then it isn’t a wild assumption to suggest that you might learn from the most prominent cooks around – celebrity TV chefs. A nutritional comparison of the two doesn’t seem outrageous.

Presumably you know what our findings were? We found that, on a number of nutritional metrics, ready meals did better than celebrity chef meals, but neither of them did very well. The ready meals were less unhealthy than the celeb chef meals, but it would probably not be right to say the ready meals were healthier than the celeb chef meals.

I knew what was going to happen. I didn’t have any idea how to stop it happening. Perhaps there was none.

The BMJ went to town promoting our paper. The media loved it. We got on the Today programme headlines, the paper was covered by loads of newspapers and not just in the UK, all three of us spent most of publication day doing interviews with just about everyone and their dog. But however much we tried, it was very difficult to get the message across that neither group of meals were particularly good for you – we were definitely not saying that ready meals are the way to go. But that’s the message that everyone seemed to hear.

Ho hum. What can you do? The media circus would move on. No-one would remember. And presumably any colleagues who would, might take the time to read the paper (or at least the abstract), and not just go on what was in the newspapers?

I can understand why people went for the “ready meals healthier than celeb chefs” headline and why that then prompted all the various responses it did. But I was most bothered by Monty Don’s response. And not just because I’ve always thought he seemed like a nice, and thoughtful, guy.

Do lots of people think scientists should only do, and publish, studies that come up with the ‘right’ results? That we should make sure the measures we use are designed to come up with those ‘right’ results? What about Ben Goldacre and the All Trials campaign for open data and publication of all trial results – not just positive ones? How does that match with this attitude? Or maybe I’m assuming that Monty is more representative of ‘the public’ than he really is.